An invitation: The Uluru Statement from the Heart. The 2023 Voice Referendum

Speaking on the lands of the Kaurna people, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese today announced that the 2023 Referendum on an Indigenous Voice to Parliament (the Referendum) will be held on the 14th of October 2023.

The Referendum will ask Australians if the ‘Voice’, a body providing advice to the government on issues impacting Indigenous people, should be enshrined in the Constitution. The ‘Voice’ is the first pillar of the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart is the culmination of 13 Regional Dialogues with First Nations people which arrived at a consensus about what constitutional recognition should look like. The Statement is an invitation from First Nations people to all Australians, imploring collective efforts towards substantial reforms that pave the way for the realisation of Indigenous rights.

This brief summarises the catalysts behind the formation of the Uluru Statement, the operational framework of the upcoming referendum, and the objectives underpinning the envisioned “Voice.”

Background

History

First Nations people were excluded from the original drafting process of the Australian Constitution in the 1890s. They were also excluded from the law-making power of the new Federal Government of Australia and were not included in the population count that determined the number of seats in the Federal Parliament. The 1967 Referendum removed these exclusions but failed to recognise First Nations people in the Australian Constitution.

In the 1990s there were calls for a statement of First Nations recognition to be included as a preamble to the Constitution. Prime Minister John Howard put forward a preamble with some words of recognition at the unsuccessful 1999 Referendum.

2010’s

In 2012, Reconciliation Australia established the Recognise campaign to advocate for constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. The campaign had bipartisan political support and developed considerable public support. A Referendum Council was created in 2015 to develop detailed advice regarding steps towards a referendum.

A series of meetings convened by the Referendum Council culminated in a large, four-day Convention at Uluru in May 2017. The Convention drew upon work done over the past few years by the Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians and the Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

The Convention opposed the existing calls for constitutional recognition in favour of more meaningful and substantial recognition. The Melbourne Dialogue stated:

“Aboriginal people will not accept a feel-good, symbolic stamp on a fundamentally unfair system. The system needs to be improved. We need to change the way we do business in Aboriginal affairs. Constitutional recognition must mean real reform. It must create a genuine paradigm shift, or Aboriginal people will reject it.”

The Convention accepted the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

In 2017, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announced his Cabinet rejected the Uluṟu Statement from the Heart.

States and Territories

Following this rejection at a Federal level, most state and territory Governments in Australia began implementing elements of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. In Victoria, the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria (The Assembly) is the democratically elected body of Victorian Traditional Owners tasked with building a framework for treaty-making. The Northern Territory, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, New South Wales and the ACT have all committed to their own version of a state-based Voice, Treaty, and Truth and are at varying stages.

While Western Australia has not committed to a formal treaty process, Settlement Agreements such as the Noongar Settlement and the Yamatiji Settlement are considered to be treaty equivalents. The South West Native Title Settlement (the Settlement) formally recognises that, since time immemorial, the Noongar people have maintained a living cultural, spiritual, familial and social relationship with Noongar pooja. It is the largest native title settlement in Australian history.

Yamatji Nation Indigenous Land Use Agreement supports Aboriginal empowerment and recognition and includes a diverse range of benefits, with a strong focus on economic development, supporting the vision of the TONT to negotiate a settlement that would build a sustainable economic foundation for Yamatji Nation members, ensuring their active participation in the regional economy, today and into the future.

2018- Now

The Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Peoples was created in March 2018 and delivered its final report here. The co-chairs were Julian Leeser MP and Senator Pat Dodson. The key recommendation was for the government to initiate a process of co-design, but it also re-opened an option for progress towards constitutional change.

In his acceptance speech following the 2022 election, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese committed to implementing all three pillars of the Uluṟu Statement from the Heart, beginning with a constitutionally enshrined ‘Voice’ to Parliament.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart

The Uluru Statement from the Heart calls for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Australian Constitution and a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making and truth-telling between governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. ‘Makarrata’ is a multi-layered Yolŋu word understood as the coming together after a struggle.

The Uluru Statement affirms the sovereignty and the long and continuing connection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with the land. It also comments on the social difficulties faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the structural impediments to the real empowerment of First Nations Peoples.

The three key pillars of reform in the Statement are:

- Voice – a constitutionally enshrined representative mechanism to provide expert advice to Parliament about laws and policies that affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

- Treaty – a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations peoples that acknowledges the historical and contemporary cultural rights and interests of First Peoples by formally recognising sovereignty, and that land was never ceded.

- Truth – a comprehensive process to expose the full extent of injustices experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, to enable a shared understanding of Australia’s colonial history and its contemporary impacts.

The focus of the referendum pertains solely to the initial component of the Uluru Statement – the Voice.

The representative body providing a First Nations voice will be a constitutionally entrenched institution that enables Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to be formally consulted on legislation and policy affecting their communities.

While some conservative voices are calling for a legislatively based Voice to Parliament, advocates for the Yes Campaign maintain that the Voice should be built into the Constitution so that it cannot be changed at the whim of the government of the day. Each of the five previous mechanisms that have been set up by parliamentary processes to help deliver a voice to Indigenous Australians have been abolished by successive governments.

The Voice Referendum

On 19 June 2023, Parliament agreed on the constitutional amendment and question.

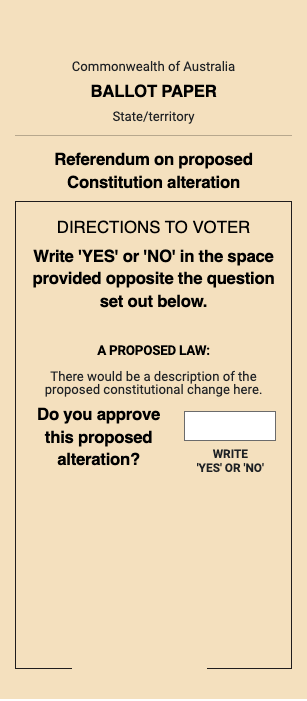

The question on the ballot paper will be:

“A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

Do you approve this proposed alteration?”

On referendum day, voters will be asked to vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the question above.

If a yes vote is successful, the following lines will be inserted into the Constitution:

“Chapter IX Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

129 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice

In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia:

- there shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice;

- The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

- the Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures.”

The constitutional provision only mandates that the Voice embodies an “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice,” leaving the intricate guidelines for its structure to be crafted by the parliament. The identity, experience, culture and views of First Nations across Australia are complex and diverse, thus, the composition of the Voice will be determined in close consultation with local Indigenous communities and will require ongoing monitoring, input and evaluation in cooperation with those communities.

By not embedding the composition of the voice within the constitution, it allows the voice to be flexible and adapt to the evolving needs of the community.

The government has committed to certain design principles that have been set in collaboration with the Referendum Working Group. These principles commit the government to a Voice that:

- Is chosen based on the wishes of local communities

- Is not appointed by the government

- Reflects gender balance and youth perspectives

- All members must be Indigenous.

The Vote

This will be the 45th referendum in the nation’s history and the first in 23 years.

Only 8 out of the 44 previous referendums have been successful and all that have succeeded have had bipartisan support.

For the referendum to succeed it needs a double majority – a majority of voters in a majority of states (four out of six) must vote yes. A majority of Australians have voted Yes in 13 Australian referendums, however, five out of the 13 did not have a double majority.

Votes cast outside of the six states, such as from the Australian Capital Territory or the Northern Territory, are counted towards the National Majority but not towards any of the state counts.

The AEC is required to distribute a pamphlet to Australian voters, containing the Yes and No cases prepared by parliamentarians who voted for and against the proposed law. Both the Yes and No pamphlets can be accessed here.

Unlike the federal or state ballot paper, there will only be one box on the ballot paper, and voters will be required to write yes or no.

Similar to a federal election, early voting booths will open a fortnight prior to the referendum date and eligible voters will be able to cast their vote via post. Voting services in remote communities will start 19 days ahead of voting day, a week ahead of when early voting centres in other localities will open.

The Australian Electoral Commissioner has stated that pre-pandemic overseas voting services will be enabled.

More information is available via the AEC website.

Race in the Constitution

A significant criticism of the Referendum is that it will divide the community along racial lines and create racial inequality.

The concept of race already exists within section 51(xxvi) of the Constitution. As initially written, section 51(xxvi) empowered the Parliament to make laws with respect to: “The people of any race, other than the aboriginal race in any State, for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws”. The Australian people voting at the 1967 referendum deleted the words in italics.

The High Court has determined that the Race Power can be used for both the benefit and detriment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. It has been used to make legislation about:

- Native Title

- Cultural Heritage Protection Laws

- The Northern Territory intervention placed restrictions on alcohol, changes to welfare payments, education, employment and health initiatives and other measures.

Its existence and breadth underscore the need for a mechanism – the Voice – to listen to the very people to whom those laws would apply.The Voice is supported under international human rights law as it recognises Indigenous peoples’ rights to political representation and is consistent with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The Powers of the Voice

Over the past five years, the concept of the voice has undergone thorough scrutiny by constitutional attorneys from various viewpoints, facilitated by the government’s Constitutional Expert Group. They agreed that the amendments would not confer exceptional entitlements upon any individual or group. The Group determined that the “draft amendment maintains constitutional integrity” and does not grant a “veto” authority or bestow “special privileges” upon anyone.

The Voice would operate in a subordinate capacity to the Parliament.

It will not possess the authority to introduce legislation in Parliament or vote on legislative matters. The body would counsel local, state, territory and federal governments on such issues impacting Indigenous Australians and the Voice will also be able to table formal advice in parliament, with a committee obligated to consider that advice.

The Parliament will maintain complete authority over its own procedures and holds the ability to amend legislation and modify protocols if it deems the interactions between the Voice and other governmental bodies are unsatisfactory. For instance, the Parliament could enact laws mandating that public officials take the Voice’s advice into consideration when making decisions. Conversely, Parliament also retains the prerogative to adjust or revoke such obligations.

Certain legislations that pertain to all Australians impact Indigenous Australians differently. Thus, it would be ethically unsound for the Parliament to determine which laws the Voice should be able to comment on. Indigenous people generally experience lower standards of health, education, employment and housing. They are over-represented in the criminal justice system nationally compared to non-Indigenous people.

Aligned with the principle of Indigenous self-determination, the Voice will have the autonomy to identify its priorities and engage more substantively on issues it determines to be critical, taking into account the availability of resources and time.

Current Polling (August 2023)

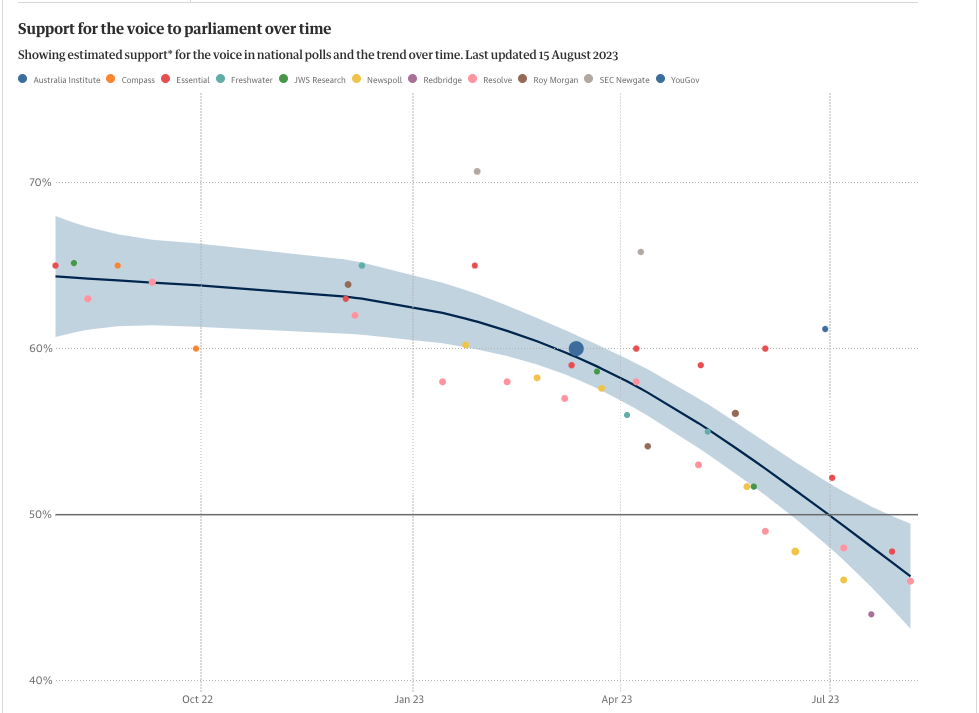

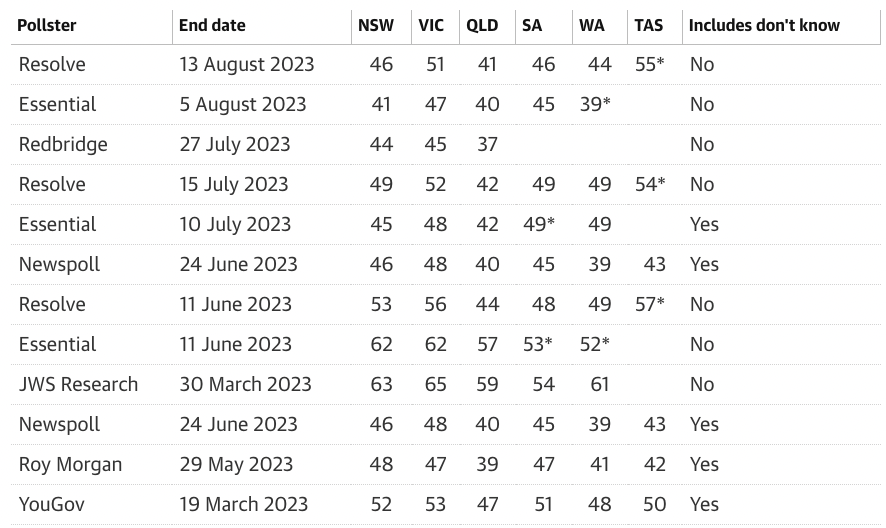

The latest polling figures and polling trends have been summarised below.

Source: Guardian Australia

For further information, please contact Hawker Britton’s director Emma Webster at [email protected]